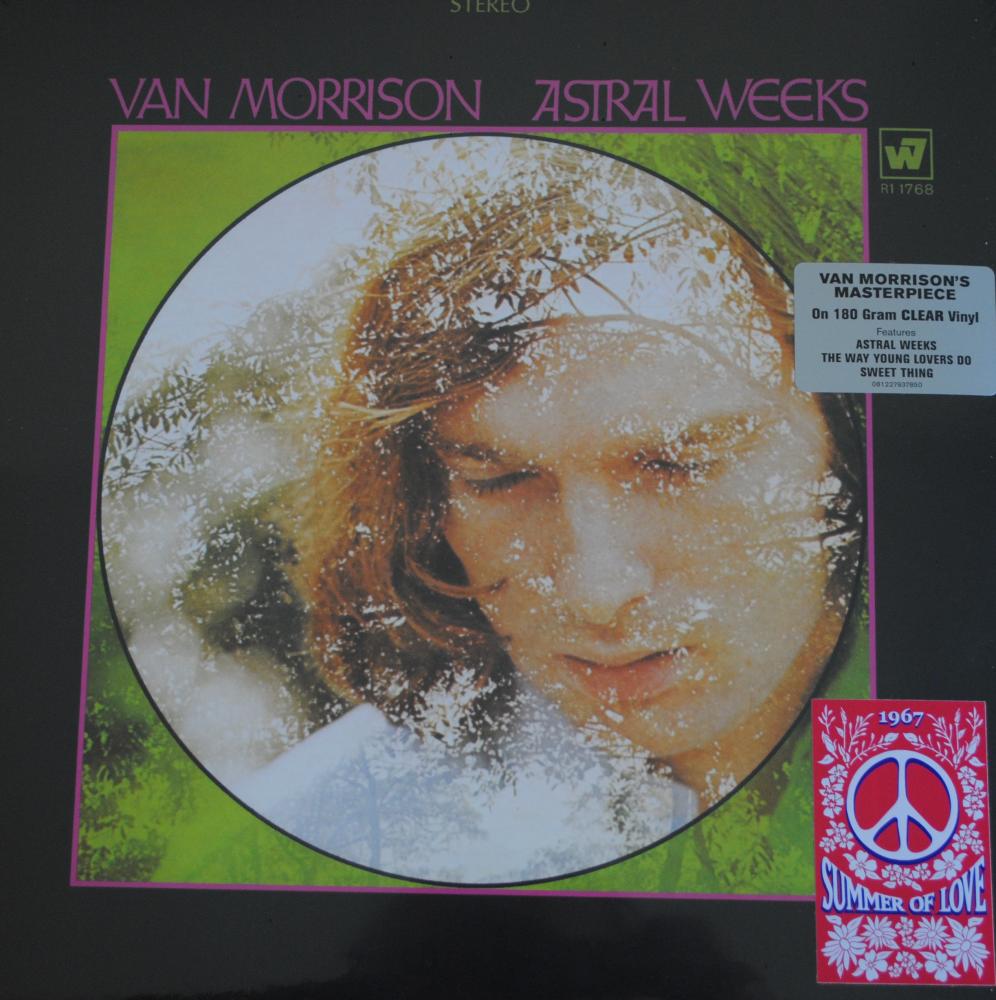

When Van Morrison first began to sketch the songs that would become his 1968 masterpiece Astral Weeks-released 50 years ago this week-he was gazing across that very divide, temporarily back in Belfast but itching to go west. But zoom out 250 million years, or maybe just 250 million miles, and the odd idea of a Belfast cowboy starts to make its own kind of sense. “The first Appalachian journey was the one made by the mountains themselves.” Most of the nicknames given to the Northern Irish singer-songwriter Van Morrison and his music seem at first to be playfully contradictory-“The Belfast Cowboy,” troubador of “Caledonia soul music” or “Celtic blues.” They are nods to his dual influences of American R&B and the older Gaelic traditions of his home, jokes about the impossibility of reconciling them. “More than two hundred and fifty million years ago the mountains of Great Britain fit together like a jigsaw puzzle,” the Appalachian novelist Sharyn McCrumb has written.

These twin mineral trails are reminders of the ordinary miracle of continental drift, the kind of thing you learn about in grade school but can so easily forget as an adult that to recall it instills a fresh sense of awe. Legend has it that serpentinite was a valuable commodity to ancient Celts and some even believed it contained mystical powers.

Beneath the Appalachian Trail, an underground thread of earth-green mineral runs from Georgia up to Nova Scotia-geologists and locals refer to it as “the serpentine chain.” It is mirrored by an almost identical vein of verdant serpentinite all the way across the Atlantic Ocean, this one running through the mountains of Ireland, Wales, and Scotland, all the way up to the Arctic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)